The casual and discreet ALAC (Art Los Angeles Contemporary), an art fair I had never heard of (but have now experienced over the weekend as eager observer and art enthusiast), contained hidden gems of masterly painted and strangely fabricated art objects. Caramelized sugar, cross-sections of animal bones, and virtual reality windows to lost civilizations hint at the breadth and scope of artists working at the fair.

Operating from the Barker Hanger near the Santa Monica Airport, the fair had a quiet and calm reunion of international galleries. A general consensus from the gallerists was that ALAC is one of the most organized and relaxing fairs to work with, especially compared to Miami Art Basel or the Armory Show. The fair had a distinct absence of celebrity showcasing and price opaqueness — art market stigmas that can distort one’s appreciation for artwork.

At the Asya Geisberg Gallery (New York) booth, artists address a common problem in art: reifying digital abstraction through art historical references. One leading artist from Amsterdam, Jasper de Beijer, fabricates C-Prints from computer generated scenes in virtual reality, 3-D scans, and shot footage from his trip to the Amazon River. Perplexed, I sought to distinguish photograph from video game, documentary from fiction, reality from fantasy. The medium sized prints challenged me on many levels, and I saw an open dialogue between artists who were approaching a single problem from various angles.

Matthew Craven, exhibiting alongside Beijer, draws upon the primacy of geometric abstraction with ink and collage paperworks. A maze of Mayan, Aztec, and other indigenous patterns interlock, resembling archeological remains disrupted by sacred art objects from antiquity. Like a poster for Anthropology 101, the images advertise a forgotten mystique, trapped in textbook flatness. Similarly, multiplying geometry is mirrored by fellow exhibitor Todd Kelley, who paints “grids,” reminiscent of carpets and quilts. Endless dots of impasto paint spread out in a pseudo-pixelation, contradicting its inherent flat design.

At another booth, artists avoid the problem of “reification” entirely by going right to the source of art: alchemy. Jedediah Caesar at Susanne Veilmetter Los Angeles featured cross-sections of animal bones floating in blood-like resin, which attracted goth and heavy metal types to the booth. An artist wearing a TOPY (Temple of Psychic Youth) Jacket and her vampiric companion examined the slabs closely, observing the “fact” of anatomy, advancing like moths to a flame. The cultural magnetism of the artworks — and that local artists were taking full advantage of the industrial facilities of East Los Angeles — was impressive.

Diving deeper with strange materials, Silas Inoue, represented by Marie Kirkegaard Gallery, combines cooking oil with caramelized sugar to create enigmatic stalagmite growths and a vitrine display of what looks like a sugary tumor floating in amber. Additionally, intense graphite drawings of wolves covered in thistle flower appear to burst from mahogany artist frames. Inoue’s earth narratives and natural preservatives evoke themes from ancient Egyptian and African art. A direct connection from natural elements (stone and honey) to spirit worlds (Afterlife) eliminates the need for an audience, or even the need to think of art as artificial, or society without art. The works inspire me to question the purpose of art, where it comes from, who is it for, and why?

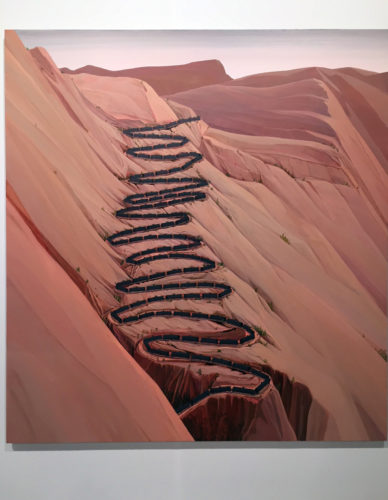

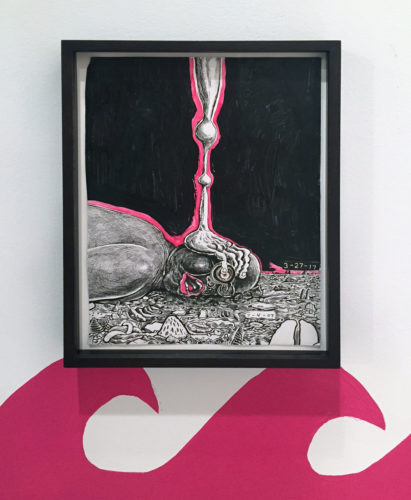

The oldest art form, painting, brought its “A” game to the art fair. Tom Laduke’s airbrush and impasto paintings, seen at Miles Mcenery Gallery, are some of the most technically advanced renderings of cyberspace I have seen in person. I also ran into Trenton Doyle Hancock at Shulamit Nazarian (Los Angeles), whose expansive world of drawings, paintings, and collages decorate an entire booth with sea-sick turbulence. Bodily displacement, heroes and villains that fit inside one another, and manipulation of text illustrate a swamped ship, full of oddballs, outcasts, and freaks. Playing with scale and direction, the ship yaws and rolls, but does not confuse its vision. Comparatively, the stark, illustrative landscapes manifest by painter Ian Davis, seen at Josh Lilley Gallery, present men standing around grocery stores and oil rigs. The men have a strange, politically neutral orientation to their environment, or perhaps we are seeing men from the perspective of nature, where politics cease to exist. The toy-like landscapes pull in audiences with questions about the future of men and the sublime, climate change: What is our relationship to nature? Can we learn from the past? Can we be saved?

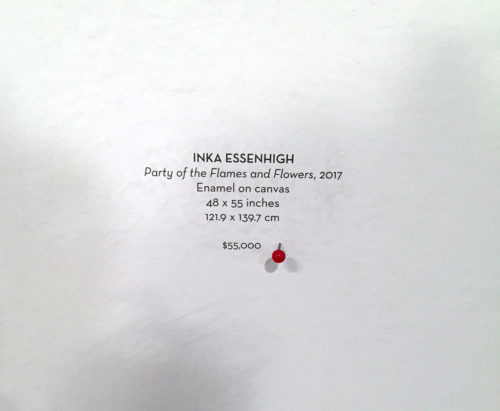

A single Inka Essenhigh painting, bearing a red dot, sold for $55,000 at Miles McEnery Gallery. The transparency of pricing may have been surprising, but it did not completely distract me from studying how the painting was made. Slick, glossy enamel over canvas, fantastic in craftsmanship and vision. I also discovered the late paintings and stagecraft by Betty Woodman at David Kordansky Gallery. Painting and sculpture synthesize into a new, theatrical mode of art-making that hangs as neither completely flat nor completely three-dimensional. Easter pinks, blues, and beiges soften a domestic scene that is both slanting and jarring at times. If Matisse ventured into sculpture, he could have a arrived at a fourth dimension resembling Woodman’s theater of art.

ALAC exhibits artists in dialogue with each other, solving problems, finding ways to challenge, perplex, and reflect upon the world. Los Angeles, in all its casualness, becomes organized at the end of the day, even if at first it seems that no one is listening. The city would dissipate if that were not true. I found what I was looking for at ALAC: artists finding new materials for new ideas, genuine curiosity, charm, a sense of order, worlds within worlds.