by KATIE CERCONE

“We Carry Our Mother’s Pain” was the comment that lingered in my mind for some time after meeting Rebecca Goyette recently and taking a walk together through Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait at MOMA. In my last studio visit with Rebecca in Bushwick, the artist had shown me a bit of the beginning of her series “Sausage Party Bride,” which revolves around experiences she had in her mother’s womb.

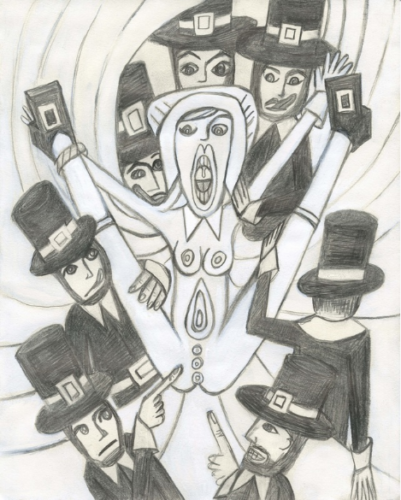

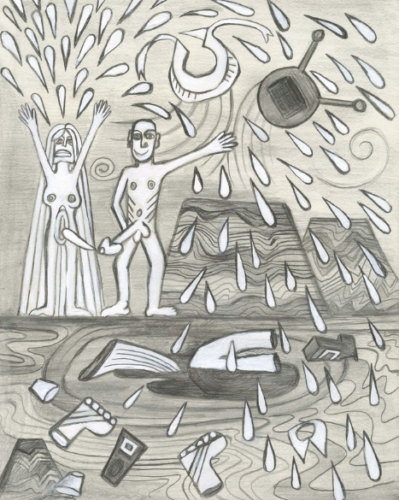

When Rebecca’s mom was pregnant with her, Rebecca’s father was using the basement as his man cave where he played pool with his drinking buddies; It was “a total sausage party,” explains Goyette. One day when her mom was fully 8 months with Rebecca, she became fed up and took an axe to the pool table and destroyed it. Rebecca had shown me the ceramic sculpture of the scene before the scene. “Sausage Party Bride,” is a medium sized ceramic sculpture of a bunch of hot dog dudes playing pool and drinking beer inside of a Bride figure’s skirt flaps. “I just think of that scene as being emblematic of my mother trying to rip through misogyny. She was literally trying to cut through misogyny. They say we carry our mother’s pain.” As a sculptor, feminist performance artist and wielder of poetic worlds strewn with animal spirit guides, psycho-sexual catharsis and auto-erotic animist innuendo, Goyette looks to the fierce French femme Bourgeois as having paved the way for artists like her.

Few would disagree, Louise Bourgeois was a monumentally important artist. Unfolding Portrait highlighted the artist’s key works of sculpture, assemblage and installation while drawing parallels to many of her unseen prints in the context of her most seminal drawings and paintings. These were works which “emerged from emotions [the artist] struggled with for a lifetime,” explains the overview of the show, with a vacuity that would have pleased no one more than Bourgeois herself. It’s like they squeezed the mother out of the mother of feminist art. As her feminist daughters, in an increasingly gender-challenged world, we’re demanding more. We’re proclaiming that aligning with female power is aligning with our emotions, our empathy, our bodies, and showing up with loving fluidity to churn the dynamic dance of creation and at times, devour it. Mater is Matter. And if there is one artist whose legacy seamlessly moved between these two concepts – Mater and Matter – it’s Louise Bourgeois.

We entered the show at Spider Mother, a colossal structure looming menacingly on the main floor of MOMA. Relative to the work, we are suddenly the dinky size of the little men playing sausage party inside the hoop skirt of Rebecca’s bride. In this article, I’ll share Rebecca Goyette’s art-historical readings of several of L.B.’s works in the show (peppered with her own personal anecdotes, stories and juicy intuitions dovetailing with the feminist zeitgeist at hand), in addition to making a comparison of the two artists works at times.

Spider Mother is from Bourgeois’s series of installations that are more or less cells. A few feature a bed or seat inside; others, found objects from the artist’s childhood – a perfume bottle, jewelry, a key. “It is a very mystical space, a magical space. It has the feeling of witchcraft in a way. She thought about the cell as being a prison and that solitary time can be confining,” explained Goyette. As an immigrant and mother of three boys, Bourgeois’ day to day involved “struggling to have time to herself to make art. Solitude was super important to her. She was trapped inside a lot of tumultuous emotions. She would sometimes go into fits of rage and smash stuff in her studio.”

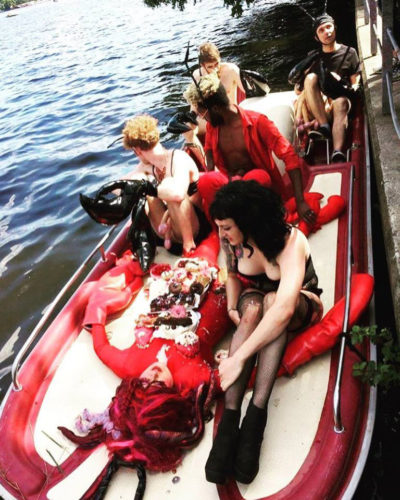

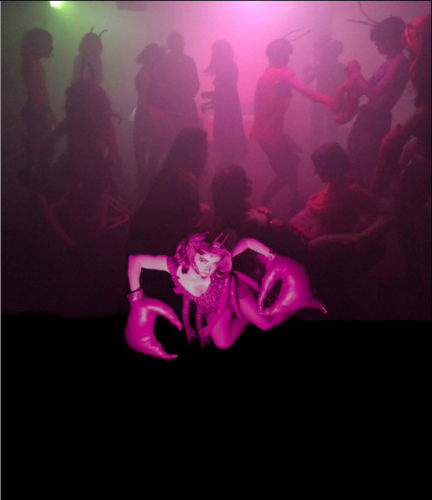

Deeper inside the Spider Mother lair we find old tapestries from her mother’s work pile. Louise’s mother and father restored tapestries for a living. Rebecca explained, “When these old pictorial rugs would get holes in them her mother’s job would be to weave back in what was missing. During the Victorian age, a lot of these tapestries had nudes in them. When they got a lot more Puritanical in Europe they decided to cut the genitalia out of these tapestries. Her [mother’s] job would be (once they started to loosen up again) to weave back in the genitalia. L.B. sites this as her interest in sexuality – noticing how crazy it is that our sexual morays keep changing, how violent that is. “Cutting out the pussy, breasts dick – it probably wasn’t even woven in their much. They’d be willing to live with a rug with a hole just so long that it’s not dirty.” Genitalia coincidentally plays a very prominent role in Goyette’s work, wherein the artist’s elaborate feature length films depict costumed adults acting out garishly animalistic mating practices as “Lobsta Bitches” and various magical hybrid breeds. A raunchy monster’s ball for the erotically inclined inspired by real science facts of the sex lives of crustaceans, her films insight the viewer (and certainly the participants in the live act that becomes the film) towards healing through mystical tableaus championing touch, play, pleasure and connection. Like much of Bourgeois work, there is a level of vindictiveness and, perhaps, revenge in Rebecca’s feminist porns. Elaborating on, and embellishing the aggressive sexual life of the lobster, she is able to flesh out all the complexity of female sexual desire which has long been left out of our classically misogynist cultural narratives.

Up top the menacing grey cage sits the Spider Mother herself. Bourgeois called the spider figure a stand-in for her mother. Reads of this piece also include cell as in biological cell, “Nature being made up of cells,” explains Rebecca. Nancy Blair writes that the Ancient symbol of the Spider – Sacred Creativity – is the Creatrix that sits at the center of her world, defining her limits, spinning her own fate, manifesting what is to come. In Native American myths, spider woman weaves the world into creation. She walks on earth and weaves her home in the sky – offering the power to bring together two worlds typical of the shaman. In Hindu myth, the spider symbolizes the Mother aspect of the triple Goddess Maya who spins the web of fate and “symbolizes the invisible magic that unites creative vision with action.” The Spider Creatrix reminds us how “simple, everyday acts of creativity” offer a “more sustaining and sensual experience in the now.” Interesting considering that L.B., like her mother, was a woman weaver. Rebecca’s final thoughts about the Spider Woman was that like all of her creative work, it represented an interior world for Bourgeois.

Sometimes in her prints L.B. included text like “I spent my life washing socks, fearful, foolish…” Rebecca explained that Louise felt locked in a very patriarchal world, one in which men did not share the burden of housework. When she and her husband moved to New York City in her twenties she never thought she could become a famous artist. “There were so few women that had any kind of fame. She had all this work squirreled away. In her early forties, Jerry interviewed to be her sculpture assistant and he found billions of drawings, prints – all this work that she had made squirreled away. He organized it.” Rebecca informed us that Louise’s emotional issues were debilitating at times. Many works communicate an overwhelming feeling of entrapment – and the last twenty years of her life she in fact suffered from Agrophobia (fear of leaving her home). She did not even attend her own solo show at the Guggenheim Museum. It was Jerry her assistant that came up with the concept of the salon, to keep her socialized. For many years L.B. notoriously hosted a salon for artist’s out of her New York City apartment. I listened raptly to Rebecca, who seemed to know every little detail of the artist’s life. “She said ‘Art is my guarantee to sanity.’ She said ‘I will not cry I will just work.’”

We walked through long halls of more drawings, prints and paintings as Rebecca narrated, “It could look like sperm or intestines, so many bodily references to the more abstract pieces.” In one work we see a pregnant figure with the baby inside of her womb, umbilical cords, the baby is screaming. “She always wore her hair very long and thought of that as a symbol of her feminine power. The umbilical cord, it becomes intestines, it becomes her hair. There are some really intense pieces in the show about motherhood.” Rebecca continues the tour through years upon years of L.B.’s drawings. “I think she felt burdened by the housework and the limitations that she thought may never lift. I think that she thought there would be no way out of her situation. Come to find out there was. She found a way to do all of this.” She found a way to make years’ worth of art that would empower women and artists the world over for years to come.

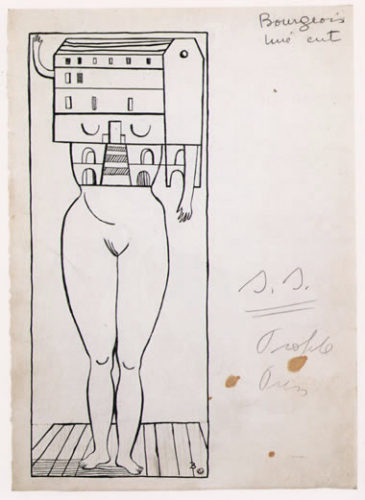

“She had strong opinions. She was really sharp witted and sharp tempered. She wasn’t like a lily in any way… ultimately she didn’t want to go anywhere but she wanted her work to go everywhere.” We approached one of her best known Femme Maison (1946-7), now a cornerstone piece of the feminist art cannon. The woman in the drawing has no head, she has no breasts, she’s just a house. Rebecca begins speaking about the figure in the drawing, as if channeling the voice of the work “She is planting herself, rooting herself in a stubborn stance, help me! Get me out of here. We do see the breasts here…This body here has the feeling of freedom. Bending your legs like that, feels like you’re about to squat, feels like dancing, feels playful. There’s a lot of contrast. Jail cell bars where her pussy would be. She found her own way to function. She found the kind of help she needed to make her vision grow… this was 1947.”

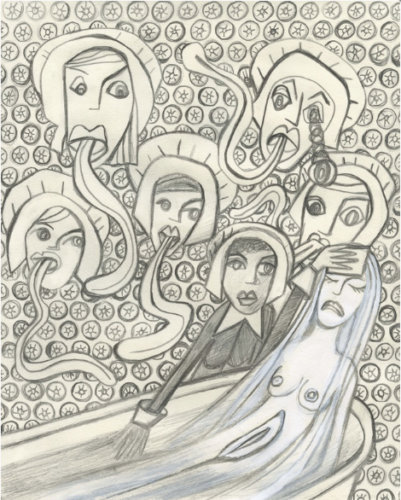

As Rebecca talks about L.B.’s drawings and prints, I can see the way that she has taken this bread trail of empowering female archetypes, etched out by the frustrated, angry, domestically-challenged Bourgeois and revived them in her work, which has meanwhile evolved to include real live human bodies, female and male, activating these tropes in real space and real time. The “women on top” narratives Goyette renders are often cloaked of course by sweetening layers of whimsy, color and absurdity, as artists tend to render their optimal dreamworlds. Rebecca explained that like many artists she could relate to the feeling of having to make work for her own personal sanity. “I need to make work for myself or I feel sick. I think that’s common to a lot of artists; I don’t feel unique in that way.”

We approach a group of works that feature the artist’s big sprawling signature. That big, infamous “L.B.” Rebecca says “When she signs it that way don’t you get an impression of her mindset? It feels a little more unhinged.” Rebecca goes on to explain how Bourgeois monograms these prints with her initials very clear L.B., juxtaposed against her father’s European monogrammed style, which she considers illegible. “She wanted to be very legible, unlike her father who was ‘hard to read’ and basically a liar.” Louise had an issue with her father growing up, as he was having an ongoing affair with her English teacher. Louise’s English teacher was more of a nanny-style English teacher, and a person trusted as a friend. Holding this secret inside for years as her father told Louise not to tell her mother ate away at the young artist. Says Rebecca, “She really resented being put in that position. That was deeply psychologically traumatizing for her. These days it’s not such an unusual story. That situation could have been ‘usual’ – and she wasn’t having it.”

Our conversation turned to the climate of the art world right now, where it feels like nearly every male-bodied person is on trial for sexual harassment of some kind. “The art world is trying to flesh out some of these stories [of misogyny]. I’ve been approached by a lot of writers lately who want to know if I’ve ever been sexually harassed in the art world. I felt like they were stereotyping me because I make very psychological and sexual work. I don’t have a story of sexual harassment in the art world. I just ended up being like ‘no comment.’ I didn’t want to downplay other women’s experiences either. A lot of business dealings in the art world feel like they happen between men drinking together. Getting really rowdy and then making deals together… There’s a certain point in the evening if you’re the only woman there…it’s not these guys are going to rape me. It’s that my gender is not part of the picture.”

We went on to discuss the shows upon shows dominated by white male painters that go off without even a forethought. Is it ethical? Is it equal? Could this be art? Rebecca remarks, “I was in a show that was Anti-Trump and I asked who are the other artists in the show, wondering and making sure that there were other women, voices of people of color. There were a couple but not very many. It was mostly white men. You guys are not only just missing the point, you are missing an opportunity.”

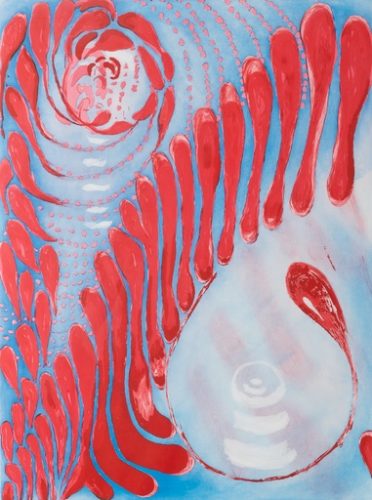

We come upon L.B.’s Paris Review. At the time literally The Paris Review was bombarding her with questions. Asking her what is the imagery? What is this all about? Rebecca says, “Sure, you can see sperm an egg, you can see breasts, you can see body parts. She got so frustrated because she felt like they were trying to pigeon-hole her as this sexual female artist. She tells them ‘but of course, it’s the inside of a pomegranate!’ and then she calls this piece Paris Review. She’s furious here.”

As for Bourgeois’s climactic spiral period, MOMA has little to say. Rebecca observes L.B.’s spirals are in fact obsessive, and related to that special alchemy artists experience in their life and work. She sprinkled them through a lifetime’s worth of artwork, sometimes scrawled rather maniacally on found items of furniture or even pieces of her own dining room table cloth. “She thinks of [the spiral] as her emotions. The spiral squeezes her. Others have seen it as a cocoon where the metamorphosis is happening. She’s alchemizing her pain into something that becomes the object. Through that she is always renewed and recharged,” says Goyette. Nancy Blair weighs in similarly here as well, “Spirals of every variation are an age-old symbol of the Goddess… they represent birth and rebirth: being, knowing and becoming.”

According to archeomythologist Marija Gimbutas, the spiral is one of the first and most primary hieroglyphics of Neolithic Goddess worship. Gimbutas, who dedicated several decades of her life to uncovering the major aspects of the Goddesses of the Neolithic as they appear in visual form when the very first sculptures of bone, ivory, or stone appeared (around 25,000 B.C.) demonstrated within her much lauded and thoroughly academic research how the Goddess and her basic functions as Giver of Life, Wielder of Death and *Regeneratrix* appears in the earliest of all Art manifested by the signs of dynamic motion: whirling and twirling spirals, winding and coiling snakes, and circles made more pronounced by crescents, horns, sprouting seeds and shoots. The snake or ouroboros (snake eating its own tail – the big kahuna infamous of spirals) is a symbol of life and energy regeneration as well as a primary symbol of Yoga.

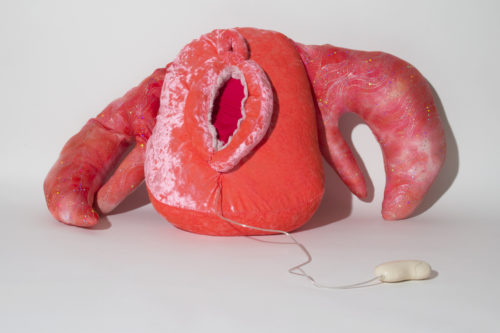

Over time, Rebecca’s Lobsta Labia Avatar began to take on elements of Octopussy, becoming a hybrid of sorts that also now conjured up imagery of mondern day Hentai tentacle porn, and as Rebecca educated me, how female Octopuses die when they give birth. “There is a gravitas to this oceanic mother’s relationship to her role as mother and her own dying process,” says Rebecca, whose exploration of the sex lives of these various ocean creatures has allowed her to reveal the death-life-rebirth cycle ascribed to the Goddess in full, scientific relief. Her sculptural “Dentata Umbrella,” which I later viewed at Untitled Space in Soho, hangs above our head in a way to accentuate its giant, salacious tendrils. Lending the experience of being enveloped by the Divine Mother, including the razor-sharp teeth of her deadly vagina dentata; and at other times, suggests Rebecca, “she doesn’t care to let us all in,” as she “flexes her omnipresent femininity.”

Along those same lines, Rebecca points out how many of Bourgeois’ works have almost a Venus of Wildendorf, or primitive Goddess vibe, despite the fact that L.B. seemed to hide her feminine attributes at all cost. “Mostly as a measure of protection in a very sexist art world. She was a very petite woman and had extremely big breasts but you don’t see it that way in very many pictures because they portray her as a really serious artist all the time.” Ultimately, Rebecca’s convinced of nothing more than the fact that L.B. lived by the notion that you could get unstuck by making art. We discussed how today the healing has to go deeper than just 2-dimensional drawings squirreled away in fits of rage or even colossal art sculptures. Today we understand that you have to do the healing work physically – in your body, mind and soul.

Contemporary “witch” figures like the revered Starhawk, who played a major hand in the revival of wicca or “Goddess Worship” on the West Coast in the 70s and 80s, have revived the spiral symbolism in the form of dance. Starhawk’s book The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (1979) breaks down the spiral dance as a group embodiment practice based in the linking of Goddess spirituality with feminist political activism. Starhawk writes that the old symbols are not just symbols, they are “channels of power.” Under the banner of the three principles of Goddess religion – immanence, interconnection and community – her work with the spiral dance became an annual ritual in San Francisco drawing together thousands of neo-pagans to dance the double spiral each year. Rebecca in turn, as you may know very well, has a whole body of work about witches, including her recent, critically acclaimed solo show “Ghost Bitch” at Freight and Volume. Part of Rebecca’s personal lineage as a creator involves healing trauma around her great ancestor Rebecca Nurse who was burned as a witch.

“I wonder what sign Louise Bourgeois was?” I look at Rebecca; it suddenly feels like the most pressing question of all time, and the only thing Rebecca doesn’t know. Google unriddles the Sphinx. L.B.’s a SAGITTARIUS, a sign that marks the beginning of transpersonal consciousness, “the Guru” whom emerges after the Scorpio sign of Death.

Rebecca goes on to elate her experience attending one of Bourgeois’s salons. “My friend told me she liked it if you brought chocolate and cognac so I brought chocolate and cognac. You could bring one work of art.” At the time Goyette was living in Jersey City, mostly painting crazy Alice Neel type paintings and doing spoken word frequently at the Water Bug Hotel for a regular group of young, fun peers that prided themselves on all being “stumbling distance” from the bar. Rebecca brought a long scroll from her first solo show, also at a nearby bar. It was a “Last Supper” scene designed to go behind the bar with the theme being “Last Call.” The whole scene was pimps and hoes. “It was rolled up as a scroll. I had this plan to unfurl it, the piece was pretty thin and really long so by unrolling it in the room I knew people were going to have to hold the other end, it was going to be really dramatic… I was thinking like a performance artist already.” Rebecca recalls L.B. taking a look at the painting and saying, “This is a good painting; it looks very narrative. Do you also write?” Rebecca answered yes and Louise encouraged her to read a poem.

Rebecca read a poem aloud and Louise starts clapping, she cheers “Encore! Encore!” very aggressively in her French way. Rebecca reads another poem and L.B. continues clapping intensely. She gets everyone to clap. “I am getting into it now, it’s like the performer is coming out. I do like 4 or 5 of them and then she says do one more and then I look in my book and I’m like mother-of-god it’s such an embarrassing poem! It’s about an ex-boyfriend that had a really hairy back and a concave chest but he was cute. I turned beat red. I was getting so nervous. I was sweating and she could see this and she was like ‘Come on now, read it!’” Rebecca let out a sigh of relief at the end as Louise chides, “So that made you feel vulnerable didn’t it? That’s how you should always feel when you’re making your work.” Rebecca never forgot that. “I really do try to make a practice of revealing something about myself in each work that makes me feel embarrassed. I’m not going to ask people to perform with me if I’m not implicating myself the most. In performance sometimes they call it playing the role of the holy fool… that poem that you’re hiding has the nugget of truth in it. I got a lot out of that conversation. It was helpful for me to see myself through her eyes.”

In one of MOMA’s upper floors, Bourgeois’s arch of hysteria pieces cry forth. We see Bourgeois herself sitting in a chair with her son and his endless umbilical cord, channeling Mother Mary before she was sexless, channeling Egyptian Isis Queen Mother, throne of heaven. Rebecca explains that with the arch imagery, Louise was most likely commenting on the psychological double standards that applied to women in those days. “They would always accuse women of becoming hysterical. If women have an emotional trauma that’s what we get called. Men never get called that. She was prone to fits of rage. She didn’t like that people would assume it was because she was a woman.” Rebecca made a corollary here to the hoodoo carnivals in Haiti where arching your back is a symptom of getting possessed by the spirit. She explains the arch is popularly linked to hysteria, drug use, spiritual and psychological out-of-body experience. “Sometimes people even get locked in certain positions because their emotions are more strong than the physical frame.”

In the next room, there is a solid gold casting of L.B.’s sculpture assistant Jerry, suspended in flight, his metallic gold body arching through the air. Rebecca connects the dots: “She was trying to show that a man could be hysterical by literally putting him in that position. A feminist read on this: in the history of art, it’s usually the female subject and the male artist who renders that subject. She is flipping it. It also wasn’t very common for female artists to have an assistant because we’ve never been paid as much as men in the art market for our work. The fact that she had her assistant make a sculpture of himself is really such a nice art history joke. Severing his head.” Rebecca likens the work to Greek sculptures that reveled in the perfection of the human physique. She mentions that similar to the rugs Louise’s Mom labored over, Greek and Roman sculptures would get their penises cut off during certain periods in history when the body became risqué. Rebecca informs me “The penises ended up at the Vatican, numbered. When I was in Rome I saw all these sculptures that were missing the penis. They’re in the Vatican in the Pope’s inner chamber.”

I ask Rebecca to make some more connections between her work and L.B. I’m curating a show with her work next month in the UK at Karst, and am super excited to offer the UK premier of her new Lobsta “porn” shot in Berlin “Crustacean Temptation.” Rebecca relates herself to Bourgeois legacy in this way – “I tell a lot of stories about my childhood trauma. I sculpt ceramics, and also make costumes, drawings and paintings. When I do my video works, I’m working with other people and I’m improvising with them. I do these shared experiences with people but I’m also getting people to help me tell my stories. Some are really painful stories. My Ghost Bitch dramas deal with ancestral trauma – my great times eight grandmother being Rebecca Nurse who was hanged as a Salem witch.”

Snaking back to the legendary L.B., Rebecca concludes “I feel connected to the idea that art is my guarantee to sanity. I have to make work to feel sane and to feel a sense of equilibrium within myself. I also like the people involved in my work to feel a sense of transformation or alchemy. Even though my works get read as very sexual – sexuality is a big part of my visual language – it’s also about grappling with all the aspects of sexuality. The pain and the pleasure of it. Sometimes things can really flip on a dime. The hairy back. The chipmunk fetish. Sorry guys.”

Goyette’s “Dentata Umbrella” will be overlooking our I AM MY OWN PRIMAL PARENT exhibition this month at KARST in England, where we will also do a screening of Crustacean Temptation (2017). Her latest film, Crustacean Temptation was based in Berlin with support from the curatorial team EVBG. The film is an experimental travel sex video casted partially on Tinder, and follows the group romp of predominantly young singles from Berlin’s club and LGBTQ kink scenes coerced into a co-created space of chemistry, leisure sports and lickable delectibles where Goyette’s sadomasochistic Lobsta Labia avatar rules all. Learn more karst.org.uk/ and follow Rebecca on Instagram @rebeccajgoyette

Bibliography

Conversation with Rebecca Goyette December 11, 2017

Amulets of the Goddess: Oracle of Ancient Wisdom (A Complete Divination Set) by Nancy Blair California: Wingbow Press, 1993

The Language of the Goddess Marija Gimbutas New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989, p. xix

“Speculation About Why A Female Octopus Dies After Her Eggs Are Hatched,” Wikipedia