This show of large-scale works do not emphasize geographical particularity in any way; instead, they reflect his ongoing interest and exploration in regard to human themes, in ways that cannot be tied easily to either Asian or American culture. The works, mostly a mixture of abstractions made up of what look like small figures, and then also images of the small figures that line up in rows by themselves, feel a bit distanced emotionally, as if Choi were trying to pull his thoughts together about our general condition. The feeling, generally, of the work is one of nonobjective schematic design and a sense that humanity does not easily rise to heroism not easily forgotten. Basically, Choi invokes patterns that are memorable for their archetypal grace. Small figures are repeated to the point where the composition becomes large with them. The figures, in just about every pose possible, reiterate the physical possibilities of the body–and by extension, the metaphysical implications of our species’ existence. At the same time, the patterns enact simple, even primitive arrangements meant to capture the eye of the audience.

In Stories in Lifetime II (2019), the central image, one of three, consists of a flag-like extension, with a dark-blue background, on which two circles of small gold stripes are centered, flanked on either side by horizontal rows of figures in every sort of position on a field of white. As a design, it works marvelously well; as a statement of humanity it achieves equal success. The dark-blue central panel with the two gold circles is strikingly effective; it offers a simple, but powerful pattern made more complex by the intricacies of the figures on either side of it. The figures themselves seem to be representative of a common humanity, enacting poses that differentiate one from the next even if the overall atmosphere is one of common humanity. Korean artists often have an excellent design sense, and Choi is no exception. Perhaps the circles, for many cultures a symbol of infinity and grace, are intended to stabilize the various poses of people available to us on the panels flanking them. Like most of Choi’s efforts, this is a symbolic work of art, in which the theme of humanity intersects with abstract patterns, perhaps meant to generate respect, or even awe, in the face of unknown forces surrounding us.

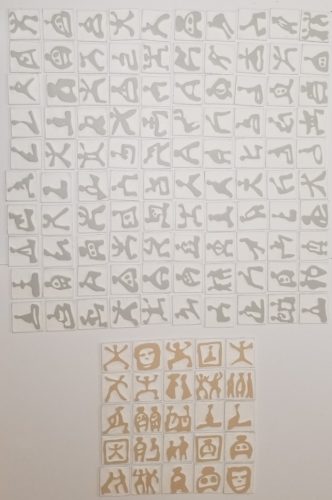

Another painting, called “Stories in Lifetime 4×4, 2019″, a grid of white squares with ghostly figures–or simple abstract designs–offers tribute to the contemporary Western grid, while the shapes within the individual squares may or may not represent the human body. They are hard to see, being only slightly darker than the off-white of the squares. Because they are ambiguous in meaning, the shapes lend themselves to the creativity of our interpretation, which may not necessarily accord with the artist’s intent (but that matters little, in the sense that we are free to view art however we wish once it has left the hands of the painter). It looks like Choi is attempting to merge figuration with abstraction, giving us a point of view that displays equally the two styles of painting. In a larger sense, it also means that he has not committed himself to a particular way of working, preferring instead set up a composite rather than a binary presentation. Doing so enables him to avoid the false dichotomy associated with one style opposing the other. In another grid, of gray forms outlined on black on gray squares, the individual shapes are easier to look at. They are more or less organic, sometimes leaning toward the human, sometimes toward the nonobjective. These shapes are a way of maintaining visual interest in light of a highly regulated set of circumstances, and evidence Choi’s unspoken but real belief that there is a continuum, imagistically speaking, that he wants to make use of, for the likely reasons of complication and variety.

A particularly nice painting is the 15-panel work called Stories in Lifetime I (2019), in which the panels are made up of small squares with red forms painted in them. Like the figures in the other paintings, the shapes can sometimes represent the human, and sometimes are simply inchoate forms. This is a kind of prehistoric writing made whimsical, in part, by our willingness to accept the originality of the imagery we see. In a fashion, we suspend our disbelief in favor of allowing the shapes to meld with or oppose each other, however it may seem to us. The complexity of the small images make it very easy to linger over their disparate displays, without which this work, and much of Choi’s art, would lose its effectiveness. Abstraction usually offers no evidence of conventional realist meaning, and realism is usually meant to be understood within a traditionally representative fashion. In the case of Choi, he doesn’t merge the forms so much as juxtapose them, side by side. In three diptych paintings set side by side (red next to gold next to deep blue), the top half is heavily painted, abstractly, with a particular color, while the bottom half is filled with rows of the semi-abstract figures that are so central to the artist’s practice. Like the other works mentioned, these three paintings can be seen either as designs or portrayals of people (at least as found on the bottom half of each work). Choi remembers that painting can communicate both thoughts and feelings, in ways that are memorable for the artist’s audience. He does this on a regular basis.

It can be asked why Choi would work in this manner. He is an Asian painter now living in America, so one would expect his work would demonstrate the hybridity of his experience. But we can’t make too much of that in the face of the work in the show. As time goes on, in art we are moving toward a monoculture, in which differences between ways of being are increasingly subsumed within a giant art world and capital economy. As time goes on, differences between cultures, even the great differences between Asian and Western cultures, look like they will be erased in favor of what some might see as a troubling eclecticism, with an opposite effect: visual uniformity. Choi’s work must be read in light of this change. His art, which is dramatic and striking, remains in our mind as a generic attempt to impose order on a world that has become both nerve-wrackingly eclectic and unsettlingly unified. Neither description is actually true, but it does seem that way. By constructing a world that intimates the troubles of non-communication, or too much communication, Choi can only suggest the imaginative loss that results from borrowing too much. Usually great movements in art have stemmed from prior strengths within the single culture originating the major work from within, but that now has changed–ever since modernism and, especially, the ubiquity of the Internat. Strangely, eclecticism has become a force encouraging the uniform, but painters like Choi remind us that, every once in a while, art combining influences can serve as a light in the midst of a very dim atmosphere. This is what we get from his show.

Janghan Choi, educated for both his BFA and MFA in Korea, now resides in Virginia.

KCC Gallery (100 Grove Street, Tenafly, NJ) is pleased to present the Solo exhibition “Janghan Choi: Abstraction of Human Life”. The show will run from December 10, 2019 – January 10, 2020.

KCC Gallery (Korean Community Center): 100 Grove Street, 2nd Fl. Tenafly, NJ 07670, Suechung Koh, Exhibitions Curator, 201 724 7077 or pariskoh@gmail.com