“Freiheit”, Freedom, is a central concept of the complete work of the painter, of German origins, Max Ernst (1891-1976). Man’s free expression through spontaneous and irreverent artistic expression, and freeing Art from a certain aesthetic formalism, especially through the arbitrary association of images and distinct realities, are the artist’s ambitions.

Max Ernst is a Renaissance man, a lover of culture in every aspect, an omnivore of knowledge. He developed his language throughout his artistic career, but it is above all in his youth that he blatantly makes use of stylistic elements from painters from different eras. References to the Italian Renaissance by Giovanni Bellini can be identified with “Allegory of virtues” in “Oscillating Woman” of 1923 and to the German one by Matthias Grünewald with “The temptation of San Antonio, The Isenheim altar” in “The Angel of the Hearth , The Triumph of Surrealism ”of 1937. Elements of Caspar David Friedrich’s Romanticism can be found with“ The cross in the mountain” in “The whole city ”of 1936-1937.

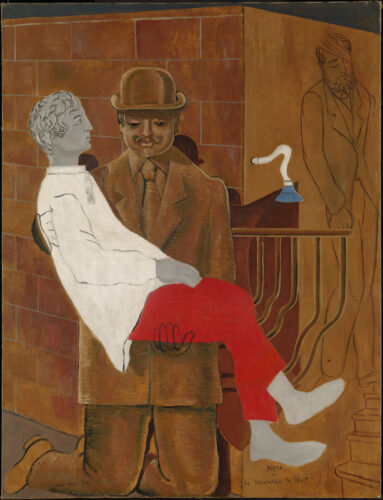

In his works, moreover, we can see hints to the works of his contemporaries such as Pablo Picasso of the Cubist period, the abstractionism of Paul Klee and the Art Brut of Jean Dubuffet, but it will be above all the Metaphysics of Giorgio De Chirico to leave an imprint important. With “Pietà or The Revolution the Night” of 1923 (PICTURE), Ernst must have seen some paintings by De Chirico such as “The Child’s Brain”, “The Returning Man” and “I’ll Go … and the Glass Dog”, but perhaps also a René Magritte for that typical bowler hat. The viewer recognizes three male figures and yet with hesitation can give an ultimate interpretation of what the roles of these characters are in the narrative of the picture. One man is drawn in the background, another, on his knees, looks like a relief on the wall whose hands are drawn on the body of the third man, sitting on his lap in the manner of the child Jesus in this unsuspected Pietà. Dressed in a white shirt and red trousers, the body of the latter figure is also sculptural yet extraneous to the background of the painting as if to want to come out of it to embody in human.

Max Ernst is a Renaissance Man also for his passion for literature (Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting, which inspired him the idea that the artist is not an author but dominated by the observation that resulted in the styles of frottage and grattage ), the romantic poetry of Hölderlin and that of Rimbaud, Nietzsche’s Nihilism, Guillaume Apollinaire’s Surrealism, the anthropological studies of Claude Lévy-Strauss and even Dylan Thomas). Max Ernst is interested in alchemy (as is evident in “Men Will Know Nothing” of 1923) (PAINTING), he knows the mythology and traditions of remote populations including the Hopi, one of the tribes of America.

Max Ernst is known for developing his own styles such as when he praises the beauty / majesty of nature with frottage (the rubbing of paper superimposed on wooden surfaces to evoke their organicity), grattage (the removal of a surface to reveal the one below), and the decal (the addition of bulky materials to the flatness of the canvas). These artistic forms were some of Max Ernst’s innovations, as well as dripping (letting the color drip onto the canvas with a casual / uncontrolled / arbitrary gesture) then masterfully used by Jackson Pollock (see Ernst’s “The Year 1939”).

He wrote about his art in the third person and sometimes signed Dadamax as another Loplop, admitting that psychoanalytic dissociation of the ego and super ego, me and the Other, explained in Freud’s writings. But Ernst had not taken refuge in psychoanalytic analysis: if on the one hand he announced in Beyond Painting, a theoretical and autobiographical writing of 1936, that “a painter is lost if he finds himself”, he did not evade civil responsibilities, but was conscious and participant often in spite of himself. He was wounded twice on the front of the First War and was interned in the Second. Only at the insistence of family and friends did he decide to exile to America in 1941. The work of art that best represents his stance with respect to a historical event was when, upset by the evident influence of Nazism during the beginnings of Francoism in Spain and inspired by Picasso’s 1937 work “Guernica” which was his most heartbreaking desperate cry, Max Ernst painted the same year “The Angel of the Hearth” with the subtitle “The Triumph of Surrealism”. PICTURE A figure dressed in colored and perhaps torn drapes, with a bird’s head but with improbable razor-sharp teeth – and a tear -, stubby legs with claws and another parasitic green beast, squirms in an apparent dance – or perhaps it is folded over, a suffering self-. It is a menacing figure that looms against the background of a natural landscape with a mountain in the great distance. As much as the distant landscape in the background recalls the Renaissance paintings of madonnas with children, the central figure is rather abstract and cartoonistic, but still recalls the work of Grünewald. The title is certainly ironic, because if an angel, this is already a demon. Ernst, during a television interview, described it thus: “It is naturally an ironic title for a kind of wader who destroys and annihilates everything in its path. This was my impression of what the world was going through, and I was right ”. It will be no coincidence that this work, unique in the entire Ernstian apparatus, was used as a poster for the anthological exhibition, a world premiere and unmissable, at Palazzo Reale in Milan (until February 2023). What would have been Ernst’s warning in the face of ecological disasters and the resurgence of the extreme right of these days?

The love for nature that must be protected and the realization of the power of art to combine the most disparate realities arose from an episode from his childhood. His father, a teacher for the deaf and dumb and a painter in his spare time, had painted a landscape with a tree. Realizing that the painting represented that tree without a branch, instead of adding the branch to the painting, he took a saw and cut the branch from the tree in the garden. This and another episode, that of the death of his pink budgie on the same day as the birth of his little sister Loni, are often remembered to illustrate the founding moments of Ernst’s artistic philosophy. The juxtaposition of different elements combined in such a way as to cause a dissonant effect is typical of Dadaism and Surrealism, of which he was one of the representatives. The same episodes of his youthful biography marked the presence of forests and birds in many Ernstian works. In 1921 he painted “The word”, in 1927 the “Forest and dove”, in 1927-1928 “The Forest”, in 1936 “The nature of love” and “The nature of the dawn”, in 1940 ” Epiphany ”and in 1941“ L’antipapa ”, works in which the hymn to nature is made with the style of frottage and that of the decal. In 1969 Ernst turns his gaze from the earthly world to the cosmos with “Birth of a galaxy”, as if the end of mankind is foretold.

The Milanese exhibition displays 400 works (Dadamax from private collections and various public bodies for a first world-class anthology. The four historical periods of Max Ernst’s life (from 1891 to 1921 in Germany, from 1922 to 1940 in France, from 1941 to 1952 in America and finally his return to Europe in 1953 until his death in 1976) are well represented in the 9 rooms of the Royal Palace organized according to pictorial themes (1. The Copernican revolution, 2. Inside the vision, 3. The house of Eaubonne, 4. Eros and Metamorphosis, 5. The four elements, Air / Birds, Forests / Earth, Water / Sea, 6. Nature and vision, 7. Gestaltungslust-Augenlust, 8. Memory and wonder, 9. Cosmos and encryption).