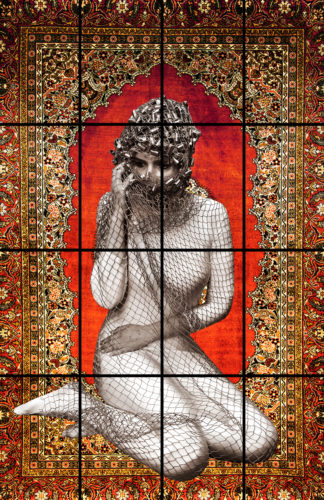

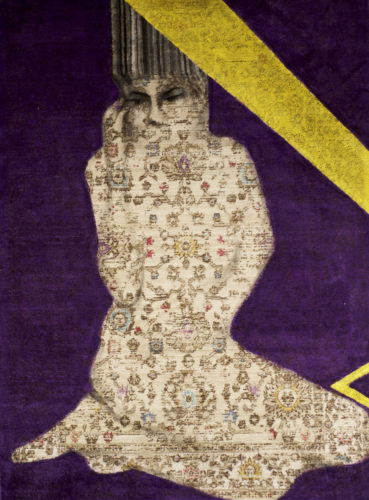

Late August, following her impressive #NoHonorKilling performance during Art 511’s flash feminist art exhibition EMINENT DOMAIN, I visited multidisciplinary Pakistani artist Qinza Najm at her studio in Hell’s Kitchen to explore some of the deeper messages in her work. Gender, sexuality and (em)powerment orient her practice, which these days takes the form of painting, performance, video and installation. Her large-scale paintings on Persian carpets certainly made a splash in the main gallery of EMINENT DOMAIN, with Najm’s elegant figures of Muslim women looming large against the backdrop of a now standard fixture of many a luxury home. Encompassed by a Western world that so readily embraces the surface beauty of a foreign culture while at the same time villainizes whole populations in deceitful bids for its own absolute power, New York-based Pakistani artist Qinza Najm’s work interrogates cultural power in relationship to geography and society. Her carefully considered pieces offer a natural antidote to a world ridden by racist and sexist stereotypes, prejudice and escalating Islamophobia amidst Trump. While she continues to traverse the territory of gender, sexuality and desire (as if with the fine-toothed comb of a detective or microscope of a scientist), it is Qinza’s unique ability to interweave some of the most devastating historical atrocities into her work while still painting a noble picture of humanity that presumes empathy, alchemy, transformation and change – that sets her apart.

Her works inspire dialogue within and around the Muslim world and the West, and situate the role of women in society at front and center. After curating her work into our show last July, I sat down with Qinza at her space in Hell’s Kitchen, part of the larger artist-run collaborative Prime Produce. In an interview with the artist amidst her many scintillating new works in process, I probed her about the culture of Pakistan and the expectations of women within Islamic society that inform her worldview. Given the volatile political situation in Pakistan, with ongoing riots, I was unable to share some of the aspects of our dialogue in this article for the artist’s safety. What follows is a narrative reflection of our dialogue offering a bird’s eye view into the psychic terrain of an important contemporary artist bridging two very distinct and yet overlapping and interdependent worlds.

For Qinza, who grew up in a moderately spiritual household (her father was spiritual and her mother was religious but tolerant), having a connection to a higher power helps her feel grounded. In moments of introversion, she finds herself reciting the 99 names of God listed in the Koran as a form of meditation. She also enjoys listening to Qawwali, a classical form of meditation music popular in Pakistan. A concept that comes into much of her works and the title of her series on Persian carpets, “Stretched” alludes to a corporeal, upward flowing spiritual energy we can embody. A lot of her female “stretched” figures have a certain upward momentum; “The stretch is up,” says Qinza, referring equally to a notion of higher consciousness and the formal concerns of an image maker.

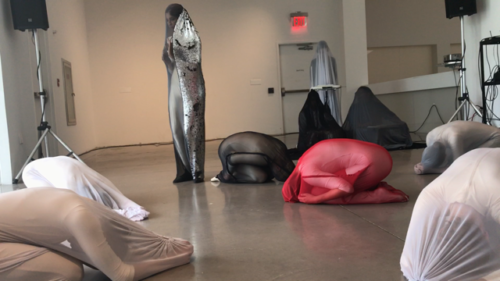

Her recent piece at the Queen’s Museum Itinerant Festival titled “Tabeedli” involved seven contemporary modern dancers wearing fabric that restricted their movement. This ensemble, which Qinza calls a “dance resistance piece,” evolved out of a series of earlier drawings in which women were depicted in meditative poses and yogic asanas. Interested in creating an immense spatial quality, the women involved responded to charcoal drawings Qinza made recently in reaction to president Trump’s ban on Muslims. Qinza recounts in a video portrait by Meticulous Media how upon hearing the news she felt a hot wave of rage.

The piece itself was titled with an older Urdu word (Tabdeeli) meant to express a notion of transformation. Restricting the dancer’s movement with binding clothing created an immense halo of tension, and yet, no matter how much each dancer’s mobility was restricted “they still found a very unique and creative way to express themselves and still… [pushed] against the boundaries that woman are put into.”

For Qinza, who grew up in a nation formerly part of India, yoga is for her a symbol of the body’s freedom of movement. Stretched figures appear in Qinza’s paintings on carpet as well as in live performance, dancers stretch from within their cocoon of sheer fabric. It refers to both the literal, physical aspect of stretching (creating space in the body between muscle, sinew and bone) and stretching in the expansive metaphysical sense, our human evolutionary impulse.

In 1947, Pakistan separated from the British colonial territory of India and gained autonomy as a distinct Muslim nation amidst religious war played out by Hindu and Muslim groups. Britain afforded Pakistan its Muslim country, given that it was able to withstand the bloody, holocaust-like genocide that ensued amidst the redrawing of state lines. The great suffering and loss to countless families was a fact which Britain has been careful to sweep under the (Persian) rug. Today, reflects Qinza, “Yoga is not something you can do in every community.” In Pakistan’s cosmopolitan Lahore, much like New York City, yoga studios open to mixed groups of both men and women are common, but the cost of admission excludes many. In other, poorer areas, yoga is simply not available. “In Pakistan, there is a very pronounced class system – which is here too, but I think it’s more subtle,” explains Qinza. Class is another important thread that emerges in her diagnosis of the way in which gender, sexual violence and abuse of power function in Islamic society.

Yoga is not the only form of physical movement restricted for some Pakistani women. For her live performance during EMINENT DOMAIN this past July in Chelsea, Qinza let her presence drill through the space of the former Robert Miller gallery. To the tune of hundreds of metal bullets slamming the floor, her rhythmic ode to the victims of honor killing echoed through the spacious interior as the packed hall of onlookers parted to make way for the spectacle approaching them. For Qinza, the “chink chink” of the bullets is layered with meaning. At first glance, you notice that Qinza has wrapped the bullets around her, appearing almost fashionable in her militaristic guise – a 40 lbs. bullet-laden veil. The metal facade of the full-body armor has a distinctly aesthetic appeal that lent grandeur to the artist’s stoic performance.

Along with this aspect of physical adornment, the sound the bullets make allude to the sweet jingly of classical dancers (with rings on their fingers and bells on their toes, goes a popular folk song I recall) – their slender feet the home for hundreds of petite bells that sound as they move about. Pakistan’s General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq banned this type of women’s classical dance in the 80s during a crackdown that outlawed booze and dancing girls, managing to push the whole redlight district underground. The Mujra (Mujra in itself is a form of dance) dancers, now make top dollar dancing for gentlemen parties of the elite classes, scantily clad by Muslim standards, their beautiful faces heavily made up and stomachs visible in the style of belly dancers.

I could not help but recall the government strictures imposed on Japanese women of the 17th century, where the Kyoto government ordered a total ban on female performance. Literally “playful women, women whose feet are off the ground” were restricted within Japanese Confucian law. Which in turn, nurtured the growth of a salacious underground culture of exotic, open, sensual female courtesan figures, forbidden by law to become the prize of noble government men and officials that were above the law enough to gain the private prize of their company. Meanwhile, the shirking of feminine duties to family was a key aspect of Geisha “badness” in old world Japan. 1

“They flirt with guys, they are making them drink, and their wives or girlfriends are there, too. So it’s a very mixed gathering. They are dancing with couples and they are dancing very seductively. They are getting paid about $2,000-6,000 per session,” explains Qinza about the modern day murja. A norm behind closed doors of elite spaces, murja girls evidence a two-facedness of the culture: It welcomes the young women into the private parties of the very educated and very well-moneyed of Pakistan; meanwhile, honor killing occurs primarily against women of lower-class families, where dancing, studying or showing skin could be considered a sin punishable by stoning.

“Lack of education is a very big part of how they view and experience the world. They don’t even follow the law. They have their own village laws so if a woman does something they will call the council of elders. They decide.” Fights between villages rarely go to the police and it’s common for rivals to one up each other in awful sexual violences (including the well-publicized case of a woman by the name of Mukhtar-Mai being raped by a hot fire poker) which are always at the expense of the women. Not only that, in order for a woman to be officially raped by standard of Sharia law (Islamic Law) two men are required to see it and testify. The woman’s testimony is not valid, and in cases where there are no male witnesses it’s considered adultery, which likewise scars a woman’s reputation permanently and formally ostracizes her from family and community.

In Qinza’s work, the artist is careful to create a syncretic representation of the issues, including making relevant corollaries to horrific cases of violence we experience regularly here in America, in particular, school shootings. Meanwhile, recent upswing of women in the U.S. speaking out against the sexual abuse they experience living in a “man’s world” a la #MeToo and the truth of the horrible lack of validity given to women’s stories of sexual violence, including the recent account of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford (the Palo Alto University Professor that publicly accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault) feels very prescient to Qinza’s research-based art practice. In the wake of Blasey’s accusation, as dozens of Republicans swooped in to demean her, many Americans banned together in a powerful “I Believe Her” campaign in support of all the women who have historically been used as pawns in the game of male politics and endured maximum scrutiny when speaking up about an instance in which they were clearly victimized.

“I don’t want to create work that slaughters my own culture, which obviously has positives and negatives like each culture.” Given all the extreme issues Qinza is able to mine socially in her work, at the core, she is interested in the way in which individuals, particularly women, transform in the face of tragedy and transmute their pain into power and persevere against all odds. Her dance resistance piece Tabdeeli represented the way in which “the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts,” says Qinza. “If we are all together as men and women, as culture supporting each other, we can create a movement through these difficult challenges – But the first step is to be together.”

One of her larger series in progress speaks to how Qinza obtained her PhD in psychology before deciding to make art full time. In this video work, her interviews with women read like deep psychological studies, gently probing into the sexual violence that is very much still taboo to speak about in her culture. “It’s not as such the #metoo movement. It’s more about being able to feel comfortable enough to talk about it in the hope that other people will.” The rawness of her subjects captured with the formal exquisiteness only a true artist can achieve, lend the women, who reveal candid stories about objects they identify as “artifacts of violence in their life,” real gravity.

One woman, framed very close by the camera, wears a traditional Pakistani bridal gown and carries her wedding photo as the object of violence, having been married too young. The woman is Qinza’s cousin, and has been a source of tension within the ecosystem of family life. After being married before full maturity, Qinza’s cousin reclaimed wearing hijab and reading the Koran as a sort of self-protective stance against the societal violences acted out against her by the Islamic patriarchal state. It was her own personal choice and a source of empowerment for her. For Qinza, who grew up in a liberal modern family in which women relish their ability to dress themselves freely, her cousin’s apparently overzealous religiosity didn’t sit well. Speaking personally, Qinza explains “I had a lot of stereotypes that were negative around covering. I did a project which talks about covering called #DamnILookGood where I took selfies wearing the hijab.” During this piece, which involved the artist donning the hijab herself for a performance in Dumbo, Qinza was attacked with anti-muslim sentiments while riding the subway along the lines of “Go Home!” As a whole, the project gave Qinza a new respect for women who “choose” to wear the hijab, saying “it requires certain inner strength.” She was able to channel her negative experiences into further fuel for her work promoting tolerance of cultural difference.

Beyond relatives, other subjects of the piece include women employed in domestic roles in Qinza’s family home. One interviewee revealed that her husband was beating her and she was unable to leave because she was financially dependent. With Qinza and the support of another close confidant, the woman was able to leave for six weeks and was meanwhile coached by her friends to make important demands that were granted by her husband upon her return. Through the small, simple gesture Qinza’s art practice afforded, three women were able to deepen their sense of relationship, increasing a connective web of mutual support and trust that ended up having profound benefits for one woman facing abuse who may have otherwise been very isolated in her domestic role as wife.

This particular project marked the first time Qinza’s own mother began to respect and connect to her daughter’s creative work. “In Pakistan, if you are a doctor or a lawyer you have much more respect,” says Qinza of her former career path in Psychology. When Qinza’s mother became a subject matter of the work she was able to see it in a different light. “Now she kind of got involved in the work and had a little bit more understanding and hence some respect for what I am doing.” Qinza’s mother’s two objects of violence were her father’s (Qinza’s Grandfather’s) walking stick and shoes. It represented how he refused to let her study and married her against her will. Rebelliously, Qinza’s mom educated herself in her teens, and for this reason Qinza views her mother as a role model. During the interview, Qinza’s mom also revealed to her that Qinza had been raped during an extended visit to her Grandmother’s house at the age of 4 by a young man hired to help in the home.

Deeply moved by this conversation and the ability of Art to open social wounds where there otherwise might be no space to speak of them in quotidian daily life, Qinza channeled this experience into her collective piece about rape at NYU. She feels the dialogue she is setting off in her work can shape a healthier society which protects women and children. A large installation made in part from the clothing of survivors of sexual violence, the piece’s linkage of sexuality to violence reifies this stance as a constant thread in her work. Having been appointed as a visiting artist-in-residence at NYU, Najm explored the parallels between Muslim women’s rape trauma and the American undergraduate on-campus culture of date rape, sexual harassment and worse.

Unfortunately, the statistics are frightening in both countries. According to Women’s Studies professor Shahla Haeri, rape in Pakistan is “often institutionalized and has the tacit and at times the explicit approval of the state.” 2 The 2016 Uniform Crime Report (UCR), which measures rapes that are known to police, estimated that there were 90,185 rapes reported to law enforcement in America in 2015, and cases of unreported incidents are estimated around 431,840. Based on the available data, 21.8% of American rapes of female victims are gang rapes.

Qinza’s installation, exhibited in one of the NYU campus galleries, encompassed several items of clothing donated by other survivors of sexual violence, which Qinza arranged kinesthetically in a full scale installation involving other found objects with symbolic value such as animal pelts and boxing gloves.

For Qinza, who claims all of the freedom of a Western woman, and perhaps a man (her male studio mate in Pakistan can’t seem to stop exclaiming “Qinza has the biggest balls!”) her work very much sheds light on the outsider identity which she lives in her day-to-day. Never quite at home in her country of origin or here in the United States where she has lived for several years, her recent video series reflects on a trip back home in which she “really felt like the Other in Pakistan.” As a border-crossing culture-maker privy to both dark and light aspects of the always trammeled East/West dichotomy, Qinza makes a concerted effort to bridge the gap between the two in her work. Currently, she is in process of a series of interviews with seven American women to balance out the project and represent the full transnational conversation at hand.

“It’s an ongoing process – change. I intend through my work to provide hope and strength,” and by this Qinza means moving women out of victimhood into leadership status. “I don’t see the changes immediately, but I don’t want that to stop me from doing something. Even if it’s one person touched from this culture or from Pakistan – like the one person who works for my Mom. She would have never talked about periods, sexuality, or good touch/bad touch with her daughter.” Because of Qinza’s project, this woman was inspired to engage in dialogue with her four daughters around these seldom discussed issues. “I actually took the courage to have these important conversations with my young daughters,’” the woman told Qinza gratefully.

And it’s precisely this type of positive feedback that inspires Qinza to keep pushing her work forward and breaking through some of the deep-seeded sexual taboos of her culture. Guided by her own unique sense of faith and the spiritual, she feels newly emboldened by Art to become a leader in opening up a new dialogue for women. These conversations not only support women in achieving more autonomy over their lives, but encourage them to advocate for themselves (and each other) against male abuses of power loosely veiled behind religious and government institutions or anachronistic tribal law. Qinza’s first solo show in her home country, And All Around Her There Was a Frightening Silence, presented by Chawkandi Gallery (Karachi, Pakistan) opens November 15th.

Bibliography

Interview with Qinza Najm, August 6, 2018 at Prime Produce, Hell’s Kitchen, NYC

Artnet. “Pakistani Artists Take #DamnILookGood Hijab Selfies” Sarah Cascone, October 14, 2014

https://news.artnet.com/market/pakistani-artists-take-damnilookgood-hijab-selfies-131421

About Themselves. “Pakistani American Artist Qinza Najm Speaks Against Gun Violence in American Schools” New York, NY August 23, 2018

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mukhtar_Mai

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rape_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gang_rape

- Bad Girls of Japan Edited by Laura Miller and Jan Bardsley, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005 p. 40-42

- Haeri, Shahla (2002). No Shame for the Sun: Lives of Professional Pakistani Women (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. p. 163